In this section of the Grantville Gazette, I'll be providing some images of major historical figures relevant to the various stories in the 1632 universe, along with commentary. Eric Flint

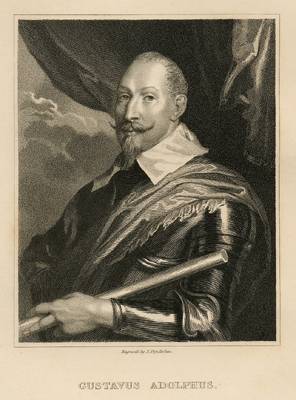

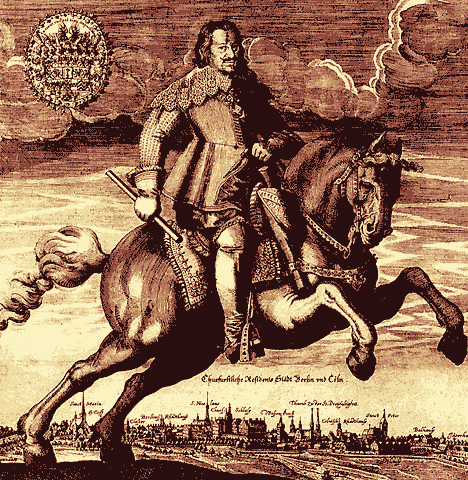

Gustav Adolf, the King of Sweden, better known under the Latinized name of Gustavus Adolphus. In real history, he died at the battle of Lutzen in 1632. In the 1632 universe, that battle never happened and he is still alive and kicking.

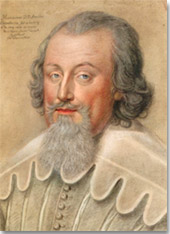

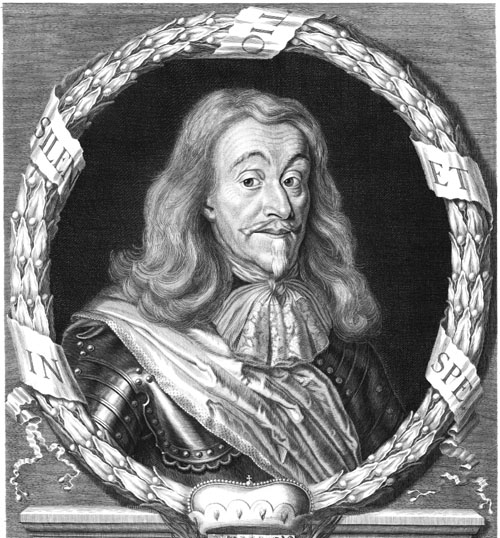

Axel Oxenstierna, Gustav Adolf's principal lieutenant and second-in-command. After Gustav Adolf's death at Lutzen in 1632, Oxenstierna became the de facto ruler of Sweden so long as Princess Kristina was a minor.

These are two images of Lennart Torstensson, one of Gustav Adolf's generals. Torstensson was younger than most—only 28 years old at the time of the battle of Breitenfeld—and a specialist in artillery. In real history, by the end of the Thirty Years War he had become Sweden's most important general officer.

Other important generals in the Swedish forces were:

Johan Banér (1596-1641)

Gustav Horn (1592-1657)

And—later in the Thirty Years War—Carl Gustav Wrangel (1613-1676).

Kristina was Gustav Adolf's only child, born in the year 1626 and eight years old when her father was killed at Lutzen. She is, without a doubt, one of the most fascinating women of the time period. Extremely intelligent and strong-willed, she eventually abdicated her throne, converted to Catholicism, and moved to Italy where she spent the rest of her life until her death in 1689.

Here are some rather more glamorous images of her:

Yup. Hollywood once made a movie about her, starring Greta Garbo.

There are a multitude of anecdotes about Kristina. Probably the most famous is that she was held responsible for the death of the great French philosopher Descartes. She invited him to take up residence in Stockholm, which he did, but then insisted that he had to meet her early every morning to discuss philosophy. In one of those early-morning treks to her rooms in the winter, Descartes took ill and died.

My personal favorite anecdote, however, is that much later in life she threw a big party at her villa in Italy when one of her friends was chosen to be the new Pope of the Roman Catholic church. The party got wild and out of hand, and Kristina ordered all the guests to vacate the premises. When the unruly and drunken guests ignored her, she summoned her soldiers and ordered them to open fire on the crowd. The death toll was eight party-goers, but she did break up the party.

This is Ferdinand II, the Emperor of Austria and the Holy Roman Empire when the novel 1632 begins. His reign began in 1620 and lasted until his death in 1637. He was the dominant political figure in central Europe at the time, as well as one of the foulest. The man was not particularly bright, prone to brutality, and a religious bigot. The little fellow with Ferdinand's hand on his head in the image on the left, incidentally, is not his son. He's a court dwarf, kept around to amuse the Emperor.

Ferdinand II's son, the King of Hungary, succeeded him to the throne and reigned until his death in 1658 as Emperor Ferdinand III.

The King of Hungary was an accomplished military leader, and, in real history, joined the Cardinal-Infante from the Spanish branch of the Habsburg dynasty in leading the Habsburg forces which defeated the Swedes at the battle of Nordlingen in 1634. The following year, Rubens painted an idealized portrait of their meeting on the battlefield, which is shown above.

Don Fernando, better known as "the Cardinal-Infante," was the younger brother of the King of Spain, Philip IV. He was born in 1609 and died early, in 1641, from an ailment diagnosed as "an ulcer of the abdomen." The Cardinal-Infante was probably the best military leader produced by either branch of the Habsburg dynasty in this time era. He was made a Cardinal of the church against his wishes, and always chafed at the status. He wanted to be a soldier, not a religious figure. Somewhere around 1631/1632, the famous Spanish painter Velasquez did the portrait of him shown above while hunting.

This is Velazquez's portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares, who was the principal government official in Spain during the time period covered so far in the 1632 series—in effect, the Spanish equivalent of Cardinal Richelieu in France or the Earl of Strafford in England.

Maximilian of Bavaria was one of the principal political figures of the time. In addition to ruling the large and important principality of Bavaria, he was also the head of the Catholic League and thus commanded the Catholic League's armies, whose principal general until his death at the Crossing of the Lech was Tilly. Early in the Thirty Years War, Maximilian also obtained the lands in the Upper Palatinate formerly controlled by the Protestant Elector Frederick, who was the shortlived "Winter King" of Bohemia and whose wife was the sister of Charles I of England. Maximillian then got himself officially appointed the Elector of that region. Maximillian is one of the most unsavory characters of the time period, and readers of the 1632 series can expect any number of opportunities to hiss and boo the fellow.

The very attractive young woman on the right in the portrait is his niece, Maria Anna of Austria, whom Maximillian married in 1635 after the death of his first wife. Maria Anna was much younger than he was, only twenty-five years old at the time of the marriage. She will figure prominently in the novel which Virginia DeMarce and I are writing in the series, 1634: The Bavarian Crisis. Both Virginia and I are firmly convinced that this sprightly lass can do a lot better for herself than Maximillian.

Johannes Tserklaes, Count of Tilly, was one of the major military figures in the first half of the Thirty Years War. He was born in Brabant in the Spanish Netherlands in 1559 and remained loyal to the Catholic church throughout his life. He was the chief general for the Bavarian forces in a number of battles in the first half of the war, including the Battle of the White Mountain in 1621 which routed the Protestants rallied under the banner of the Elector of the Palatinate, King Frederick of Bohemia, and returned control of Bohemia and Moravia to the Austrian Habsburgs. He is probably most famous—or infamous—because it was troops under his command which carried out the notorious sack of Magdeburg in 1631. Tilly actually tried to stop the massacre—as did his chief lieutenant Gottfried von Pappenheim (see below)—but the troops were completely out of control once they breached the walls of the city. The massacre of the inhabitants of Magdeburg was the single worst atrocity in the Thirty Years War, a war which was full of atrocities from beginning to end. For years afterward, Protestant troops would often refuse to accept the surrender of Catholic soldiers, replying to offers of surrender with the chilling slogan "Magdeburg quarter."

Tilly finally died in the battle fought on the Lech river when Gustav Adolf's troops succeeded in forcing a crossing, in April 1632. The depiction of that battle and Tilly's death in my novel 1632 is quite accurate historically, by the way. The only dramatic liberty I took was adding Julie Sims' sharpshooting to the scene and Torstensson's use of the American cannons.

These are both portraits of Albrecht von Wallenstein, who, along with Tilly, was the major military leader on the Habsburg side of the Thirty Years War. He was born into a family of minor Protestant Bohemian nobility in 1583, but converted to Catholicism at the Jesuit college of Olmutz while still a young man. He rose quickly in rank and wealth once the Thirty Years War began, and soon became the major mercenary general for the Austrians as well as the largest landowner in his native Bohemia. In real history, he eventually became perceived as a threat by the Habsburgs and was assassinated by soldiers acting as Habsburg agents in 1634. In the 1632 universe, his fate will be...

Different. I will say no more about that here, since that story is told in my short novel The Wallenstein Gambit, which is one of the stories included in the upcoming (January 2004) 1632 anthology, Ring of Fire.

Gottfried von Pappenheim was born in 1594 and fought against the Swedes at the battle of Lutzen in 1632. Like Gustav Adolf, he died in combat there while leading his troops. In the 1632 universe, since that battle never happened, he is still very much alive. He fought under Tilly at the battle of Breitenfeld in 1631, and then switched his allegiance to Wallenstein, whom he faithfully served until his death the following year. Pappenheim was one of the most feared cavalry leaders of the day, and was in command of his famous "Black Cuirassiers."

As a character, he has only been mentioned thus far in the 1632 series. But he plays a prominent role in The Wallenstein Gambit in the anthology Ring of Fire, and he is also a major character in K.D. Wentworth's story in the same anthology, "Here Comes Santa." (As a matter of fact, he's the "Santa" of the title. If that seems peculiar to you, well... I recommend reading Kathy's very witty story as soon as you get the chance.)

This is a portrait of John George I, Elector of Saxony, one of the major German princes during the Thirty Years War. He was born in 1585 and died in 1656, ruling Saxony for almost half a century after succeeding to the electorate in 1611. Alas, poor Saxony. I've never been able to find anything good to say about this man—although, in fairness, I should state that Virginia DeMarce thinks I'm a little too unforgiving. It is true that John George faced a very difficult situation. That said, Virginia doesn't think much of him either.

Georg Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg, was Gustav Adolf's brother-in-law. During the Thirty Years War, however, he tended to follow the lead of John George of Saxony.

This is an image of Wilhelm Wettin, the oldest of the four dukes of Saxe-Weimar. Saxe-Weimar was one of the smaller but still important principalities of the Holy Roman Empire. In effect, as the story unfolds in 1632, the rising new United States gobbles up most of the Saxe-Weimar territories. Wilhelm is a prominent character in both 1632 and (especially) 1633. All historical accounts I've read of the man make him seem—along with his brother Ernst, portrayed below—a fundamentally decent and attractive fellow, who seems to have shared relatively few of the typical political vices of the second-tier German nobility of the time. He will continue to occupy an important role in the 1632 series as it unfolds.

Ernst of Saxe-Weimar was one of Wilhelm's younger brothers and served Gustav Adolf and Oxenstierna as a very capable administrator of their conquered territories in south-central Germany. He hasn't figured very prominently in the 1632 series thus far, but will occupy a more important role in 1634: The Bavarian Crisis.

One of Wilhelm's younger brothers, Bernhard was the most accomplish military leader of the four Dukes of Saxe-Weimar. In real history, he did not betray Gustav Adolf as portrayed in the novel 1632, but his personality makes that betrayal quite plausible. Bernhard was an arrogant and self-centered man, who, after Gustav Adolf's death, tended to operate largely on his own behalf as an independent condottiere.

Armand-Jean du Plessis, Cardinal Richelieu, was effectively the ruler of France on behalf of King Louis XIII throughout most of the Thirty Years War. He was the most capable political ruler of the time, with the possible exception of Gustav Adolf. He is portrayed in the 1632 series as "the Great Villain," but that's a slanted and ultimately unfair portrait of him. In the context of the 1632 universe, it's reasonable enough, although I've taken care to give the readers as full a picture of him as possible. But in real history, he is often credited as the man who essentially "invented France" as a modern nation, and he is considered—rightly—one of the greatest figures in French history. Most of the unsavory reputation which Richelieu has today, especially in the English-speaking world, derives from the absurdly distorted image of him given in Dumas' The Three Musketeers. The man was certainly ruthless, but no more so than any capable ruler of the time—and whenever possible, he was inclined to leave the executioner's ax lying unused. His subordinates and servants were invariably loyal to him, as was the King of France Louis XIII.

The truth is, I feel a little guilty about the way I've portrayed him in the series. I did so, simply because the logic of the plot required a really capable enemy—and Richelieu fits the bill better than anyone else at the time. But I could quite easily write a different alternate history in which Richelieu was one of the heroes. It is certainly true that his French opponents, mostly the nobility clustered around the very unsavory character of "Monsieur Gaston," the king's younger brother, were a lot worse than Richelieu in every respect I can think of. Richelieu constantly outmaneuvered them in the savage political infighting in France, and sent quite a few of Monsieur Gaston's henchmen to the chopping block. I can't say I shed a single tear over any one of those rolling heads. It's just a pity that Monsieur Gaston's personal position made him immune to the ax. Really a pity. Monsieur Gaston's head would have looked splendid on a pike, if anyone wants my opinion.

These are portraits of the King of France, Louis XIII. He was born in 1601 and died young, in 1643, only a year after the death of Richelieu. One of portraits above seems to show him in the costume of the masques he was very fond of holding. The other, more pensive portrait, was done by Rubens in 1622.

This third portrait, showing Louis in armor, was done by the French painter Champagne. (Champagne also did one of the portraits of Richelieu showed above—the full-length portrait of Richelieu in his red robes of offices which is probably the most famous of Richelieu's portraits.)

Louis XIII came to the throne as a boy, in 1610, and for many years France was a regency ruled by his mother, Marie de Medici, until (with the young king's quiet acquiescence) Marie and her cohorts were ousted in a palace coup d'etat by Richelieu. His son Louis XIV is probably the single most famous king in French history, and his father Henry IV is another of the great kings of France—so Louis XIII has tended to vanish from the historical record except as a figure of ridicule (as he is portrayed in the movie The Three Musketeers).

Personally, I think that portrait of him is, at best, highly unfair, and is probably downright ridiculous. Yes, it is true that Louis XIII wasn't much interested in government and spent most of his time engaged in personal entertainment. So what? He had the good sense to find an extremely capable political lieutenant—Richelieu—and back him up whenever the political infighting called for it. Compared to the track record of a multitude of other kings in history, who were incompetent meddlers, Louis XIII looks pretty good to me. All you have to do is look across the English Channel in these same years and examine the behavior of a king who was in many ways similar to Louis but lacked his character and good sense—I'm talking about the wretched Charles I—to see that English history would have been a lot different if Louis XIII had been sitting on the throne in London. Louis XIII would have promoted a man like Sir Thomas Wentworth earlier in his career and backed him up, instead of, as Charles did, constantly undermining him and eventually betraying him altogether. (See below for portraits of Charles and Wentworth.)

But the story deepens... :)

These are two portraits of Louis XIII's wife, the Queen of France, Anne of Austria. The glamorous full-body portrait of her is by Rubens. Anne of Austria was a Habsburg princess, the daughter of King Philip III of Spain.

In popular literature and movies, Anne is portrayed as a frustrated wife married to a foppish husband and carrying on a romantic affair with the dashing figure of the English Duke of Buckingham. That portrait is best exemplified by the cinematically excellent but historically preposterous The Three Musketeers. (I'm talking about THE great version of that movie, the one starring Michael York as D'Artagnan and Charlton Heston—in one of his great roles—as Cardinal Richelieu.) The truth is that the Duke of Buckingham was the worst kind of courtier imaginable, a complete incompetent whose position of prominence was solely due to the favor of Charles I, and whose assassination in 1628 produced a giant wave of celebration all over England. (Charles never forgave his English subjects for their glee at his favorite's death, and his resentment explains much of his incredibly stupid behavior after 1628. Not that he wasn't a dimbulb to begin with.)

The truth? Well, this gets really fascinating. Although historians tend to dance around the subject, it seems fairly clear that Louis XIII was gay. It is certain that he had no conjugal relations with his wife for the fifteen years leading up to the birth of his son in 1638, the future Louis XIV. For all practical purposes, he and Anne of Austria led separate lives beginning shortly after their marriage, except for occasional formal affairs of state.

That situation created a real political crisis in France, because in the absence of an heir the line of succession fell to Louis XIII's younger brother, Monsieur Gaston. ("Monsieur Gaston" was the name he was usually known by. His formal titles were the duc d'Anjou and, later, the duc d'Orleans.) Gaston would have been a disaster for France. The man was an inveterate schemer whose sole motive seems to have been personal ambition. Not only did he engage constantly in plots, but several of those plots involved alliances with foreign enemies of France. This behavior continued throughout his life—he didn't die until 1660—and brought him into conflict with Mazarin and Louis XIV after Gaston's brother died in 1643. Monsieur Gaston would ally with anybody to grab the throne—rebellious noblemen, the Spaniards, anybody. The only thing that kept him from the chopping block on half a dozen occasions was his royal blood. More's the pity, sigh.

Not only did the situation pose a great danger for France, it posed an immediate and mortal danger to Richelieu. Because everyone knew that the moment Monsieur Gaston ascended to the French throne, Richelieu was a dead man. So... Enter...

These are two portraits of Giulio Mazarini, born in Italy in 1602 but better known in history under the Francofied version of his name: Jules, Cardinal Mazarin. Mazarini, early in his life, began a career as a diplomat for the Papacy and enjoyed a very rapid rise to prominence, largely as a result of his role in negotiating an end to the Mantuan War (1628-1630). He was something of a protégé of Richelieu's, and was eventually dismissed by the Pope because he was felt to be too pro-French in his attitudes. Mazarini moved to Paris in 1636 and became a French citizen in 1639. Richelieu groomed him to be his successor, and Mazarin did in fact replace Richelieu as the chief minister of France upon his patron's death in December of 1642. As Cardinal Mazarin, he played the same role for Louis XIV that Richelieu had played for Louis XIII, and was every bit as competent.

Now, here's the most fascinating part. A number of very respectable historians of France are convinced that Mazarin was also the real father of Louis XIV, not simply his chief minister. The official story—which is still accepted in most history books—is that Louis XIV was sired on the one and only night that Louis XIII happened to visit his wife after fifteen years of marriage where they never spent a night under the same roof. The story has it that the King was caught in the middle of rainstorm and, having nowhere else to go, found shelter at Anne of Austria's palace. One thing led to another and, voila, some nine months later the future Sun King was born.

Yup. As stories go, this one is about as threadbare as it gets. What a number of historians think really happened is that Richelieu encouraged a romance to develop between young Mazarini and Anne of Austria, and... the King chose to look the other way and give his official nod of paternity when the romance produced a child.

And, needless to say, that episode is often used to snicker at Louis XIII yet again. But I think the truth is quite different, and reflects very favorably on the king of France. Whatever injury his personal pride might have suffered, he seems to have been willing to go along with the charade in the interests of France and his own personal loyalty to Richelieu—because, with the birth of the young heir, Monsieur Gaston had the ground cut right out from under him. In short, this often frivolous king seems to have a had a degree of personal honor which is sadly lacking in most monarchs of history. If being a cuckold was what it took, so be it. Others can sneer at him, but not me.

Mind you, the whole subject is controversial among historians, and there are many who will insist that it's all a pile of nonsense. If anyone's wondering which alternative I'm going to go with in the 1632 series, be serious. I'm a story-teller, and this story is just way too juicy to pass up—especially since it is eminently plausible and nobody can prove me wrong anyway.

I should mention, by the way, that young Giulio Mazarini is a major character in Andrew Dennis' story in the Ring of Fire anthology, "Between the Armies," and will reappear in the novel Andrew and I are co-authoring, 1634: The Galileo Affair. (Coming out in April 2004.)

Finally, no set of images of major French figures of the time would be complete without:

Henri de La Tour d"Auvergne, vicomte de Turenne, is the most famous French general of the 17th century. He was born in 1611 and was killed in battle in 1675. He began his military career during the Thirty Years War, and by the end of the war in 1648 he was, along with the Swedish general Torstensson, the most prominent top commander of the period. His career continued and reached its peak during the later foreign wars of Louis XIV.

This closeup, more pensive portrait of him is by the French painter Le Brun.

Above are two portraits of Frederik Hendrik, the Prince of Orange and the third hereditary Stadholder of the United Provinces of the Netherlands. Frederik Hendrik was the dominant political figure in the Dutch Republic following the death of his half-brother Maurice of Nassau in 1625. He was born in 1584, the youngest son of the great Dutch political leader William the Silent. He never knew his father, since William the Silent was assassinated the same year he was born by an agent working for the Spanish king Philip II. Frederik Hendrik was a prominent character in the novel 1633 and will continue to figure in the series.

The woman pictured in the portrait is Frederik Hendrik's wife, Amalia of Solms-Braunfels. The Dutch had close relations with a number of German noble families, something which figured briefly in 1633 and will continue to do so in later sequels.

This last painting—I couldn't resist including it—is by the Dutch painter Van Everdingen and is entitled (hold your breath) "Allegory of the Birth of Frederik Hendrik." As 17th century rulers go, Frederik Hendrik was quite an attractive character—but he was a 17th century ruler, after all. Those lads and lassies took themselves just a tad too seriously... (Although I admit I'd get a chuckle if some modern politician came up with an equivalent campaign image. Deep in their hearts, you know they'd like to.)

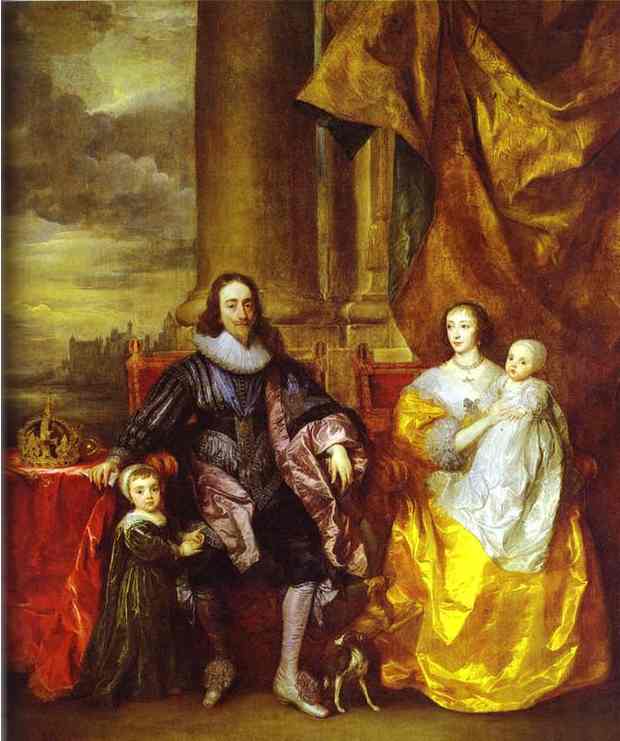

These are all images of King Charles I of England, who reigned from 1625 until his execution by the English revolutionaries in 1649. Charles I was easily one of the worst kings in British history. He combined incompetence as a monarch with a petulant and stubborn personality which led him to fixate on minor matters at the expense of major affairs of state. He showered favors on flattering courtiers and was quite willing to betray those men (such as the Earl of Strafford) who actually served him well.

The woman pictured in this portrait alongside the King is his wife, Queen Henrietta Maria, the sister of Louis XIII, King of France. She was no prize herself, sharing many of Charles' personal characteristics.

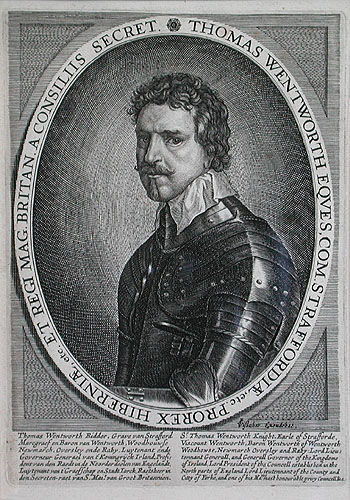

Sir Thomas Wentworth, later made Earl of Strafford in 1640, was the King of England's most capable administrator, first as Lord Deputy in Ireland (1632-1640) and then as Charles' chief minister upon his recall from Ireland. He was executed by Parliament in 1641 on flimsy grounds after Charles betrayed Strafford and signed the parliamentary bill of attainder. Wentworth was an effective but despotic ruler in Ireland, which earned him the sobriquet of "Black Tom Tyrant." Ironically, most of the hostility toward him was concentrated in the Anglo-Irish nobility, who were the descendants of English settlers.

William Laud, Bishop of London and (after 1633) Archbishop of Canterbury, was Wentworth's friend and ally. The two of them advocated a policy which was called "Thorough," which was essentially an English version of the policy being followed by Richelieu in France—the creation of an absolutely monarchy as the preferred form of government, with a clearly defined established church. Laud aroused the hostility of the English and Scot nonconformists by his stubborn insistence on rigid adherence to Anglican ritual and practice. Laud was executed by Parliament in 1645.

Oliver Cromwell was born in 1599 into a family of minor English gentry. His later rise to power was primarily due to his military abilities during the English civil war. Cromwell's cavalry played the decisive role at the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644, where he earned the nickname "Ironsides," as well as at the critical battle of Naseby the following year. He became the dominant political figure in England following his suppression of the Irish revolt in 1649-50. In 1653, he became the de facto dictator of England as the Lord Protector of the Commonwealth, a position he held until his death in 1658.

The portrait on the left is by Collingwood, done in 1651 at the height of Cromwell's power. It is the portrait that Wentworth thinks about in the novel 1633.