Euterpe, Part Five

Written by Enrico Toro and David Carrico

To Father Thomas Fitzherbert SJ,

Illustrissimus Collegium Anglicanum

Roma

From Maestro Giacomo Carissimi,

Grantville, USE

Second day of September, in our Lord’s year 1634.

Esteemed Father,

Yes, I know that I am very delinquent in responding to your last letter—no, it is last letters, since you have written three times to me since I last set pen to paper. Mea culpa, Father Thomas, mea maxima culpa. In your last letter you charged me with indolence. Acquit me, please, dear Father. As busy as affairs in Rome and Venice have been, so you say, they have been even busier in these northern lands where even in high summer one finds the air cold at times. So much has happened since my last letter, hard it is to know which theme to begin my overture. But see, my English is better, so much so that I begin to shape words like notes, this letter like a song.

I do thank you for your wonderful account of the arrival of Father Mazzare and Pastor Jones at the papal court. The people of Grantville are very interested in their affairs. Several evenings, people bought my wine at the Thuringen Gardens in order to hear of these matters. And the local newspaper even paid to be able to print the entire letter so that everyone in Grantville could read of it. Your name is now known to even the future, good Father. Please send me more such recountings. I want to know as much as the Grantvillers, for Father Mazzare is a very good man, and a priest who would stand in the first rank of any company of priests. I like him much.

So, to pick up at where we left off, as the Grantvillers would say, we must look back to January. The season of Advent was passed, as were Christmas and Epiphany. Winter had descended; winter like the people of Roma never know. Cold, it was. Very cold. So cold Girolamo Zenti, the man you know never lacks for words, had trouble describing it. But funny, I was very happy. The Lament for a Fallen Eagle had gone very well in performance a few weeks earlier. People still stopped me to say how much enjoyment they got from it. I was so lucky that Frau Marla Linder had been here to sing it. Even if it never is sung again, I heard it once in perfectness.

So my spirit was joyous, happy, almost like a choir boy who has a long holiday because the choir master is gone. But then a letter came that chilled my soul until it was as cold as midnight in Grantville.

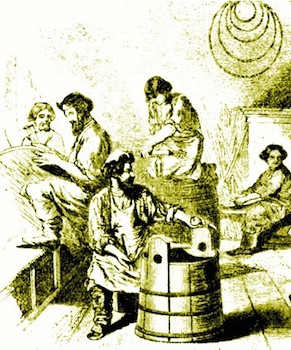

I am from Marino, you know. It is not such a grand place, but it is surrounded by vineyards, so it is a good place to be a cooper; a maker of barrels and casks. My father, Amico, and uncles and brothers, and my grandfather Carissimo before them, made barrels. Even the Colonna family, lords of that place, grand though they present themselves, bought from the craftsmen of our family. But my father, he saw that I had something in me that would not be content to shape staves of oak. He led me to the chapel-master at the parish of Santa Lucia, and thus opened up to me the world of music where I learned to shape staves of notes.

I am from Marino, you know. It is not such a grand place, but it is surrounded by vineyards, so it is a good place to be a cooper; a maker of barrels and casks. My father, Amico, and uncles and brothers, and my grandfather Carissimo before them, made barrels. Even the Colonna family, lords of that place, grand though they present themselves, bought from the craftsmen of our family. But my father, he saw that I had something in me that would not be content to shape staves of oak. He led me to the chapel-master at the parish of Santa Lucia, and thus opened up to me the world of music where I learned to shape staves of notes.

Poor Papa. We loved each other very dear, but that bluff gruff man, sometimes I would see him looking at me like a starling who had found a cuckoo's egg in her nest.

I am what I am today because of my father. And so you understand that when I received a letter from my brother Francesco I was appalled to read of my father's death. I last saw him not long before I left to Grantville. He was the same as always. But this missive from my brother told a tale of sadness.

A craftsman who works with wood works with many sharp tools, and to be cut by them is part of the game, as up-timers say. So Papa dropped a tool and put a cut in his leg. A little cut, so small Francesco said it barely bled. A cut no one would think much about. But several days later, he collapsed in the workshop with fever burning him up. Francesco said Papa said he didn't want to worry anyone. The leg was red and swollen. The next day it was turning dark, and very swollen, and red streaks were running up his leg. It was the wound rot. Francesco said that he died only a few more days later, and that it was a mercy that he did.

I read Francesco's letter to a nurse in Grantville, and she said that if Papa had been in Grantville, he would still be alive. Anti-biotics, I think she said. But Papa was not in Grantville, in cold Thuringia. He was in little Marino, south of Roma, where they have maybe heard little of Grantville, or its miracles and medicines. And I was not there to say goodbye, or to sing for him, or anything.

Francesco's letter tore a hole in my soul, Father, one that even now is there. But I have learned to live with it.

But then—ah, then I was frozen. Then I was hurting so bad. All the years I had been in Roma, I knew that Papa was in Marino, even though I could not see him. I could feel him, I think. There was a corner of my heart where he lived. But now he was gone. That corner was dark. My heart was cold. I grieved, Father. Oh, how I grieved.

Girolamo read the letter when he found me sitting like a lump and staring, not talking. His big hand rested on my shoulder, but he said nothing to me, only picked up his hat and left. He came back with Elizabeth, that is, Mrs. Jordan. She said nothing, just sat at the table with me and took my hand.

It is not clear now how long I sat. I do remember that the angle of the sun through the window had marched around like a meridiana, a sun dial. Finally, Elizabeth stood, moved to the cabinet and poured a glass of wine, which she set in front of me. "Drink it," she said. I tried to wave it off, but she insisted. "Drink it!" So I did, only it went down the wrong way, and I coughed it up all over Elizabeth and the table.

I looked at her. She was baptized in red, and the expression on her face, it was too much. I laughed, just for a moment; then I cried. I cried for Papa, for my uncles and brothers and sisters, and last for me. It hurt so bad, Father, it hurt so bad to know I would never see him again on this earth.

Elizabeth found a towel and wiped the wine drops up from her clothes, then wiped the wine from my moustache and beard. Then, gently, so gently, she wiped the tears from my face. "You loved him?" she asked me.

"Si, gli volevo molto bene," I whispered, losing my English for just that moment. I took the towel from her, and twisted it in my hands.

"Tell me about him," she said, refilling my glass and sitting across from me. And so I did. I told her everything about him; his big square scarred hands, the mole on his cheek, the crooked eyetooth, his head so bald with a fringe of gray hairs, his laugh, his eyes that would twinkle. I told her about his love for Mama, who died almost twelve years ago. I told of how he would make little jokes on the apprentices. I told her all the stories I could remember, including how he and the parish priest went fishing one day, and he pushed the priest in the stream. Elizabeth laughed at that.

It was very late when I ran the words out. It had been dark outside for a long time. I looked at Elizabeth. "You need to go to your children," I said. "But grazie di cuore for sitting with me."

"You going to be okay?" she asked.

"Si, I will be . . . not fine, but . . . I can handle it now."

"Okay." She stood up, walked around the table and hugged me. "Your dad sounds like a really nice man. I wish I could have met him."

"You would have liked him," I said, again choking a little, "and he would have liked you."

"Your memories are a testimony to him," she said, letting go of the hug, "a monument."

I finished off the pitcher of wine after she left, and went to bed.

The next days, they were hard, but I had a purpose that lifted me. When I woke up the morning after I got the letter, Elizabeth had left a note saying she would tell the school of my loss and not to come in to teach. For a moment, just one, everything I felt the day before crashed back in to me. But then I remembered something else, when Elizabeth had said my memories of Papa were a monument. I am a musician, you know, so I think things in music. And most natural, what came to me was to write a work for Papa.

I thought first to write a requiem mass. But then I decided not to. Most masses are written for and because of famous people, you know. Every Tomas, Ricardo and Enrico has a requiem mass written for them. Papa was not famous; he was a common man. Not for Papa the fame, the glory of a requiem. No, for my devout Papa, who loved the Bible stories so much, for him I would write a Passio, a Passion—the passion story from the Gospel of San Matteo.

So after a couple of cups of coffee, made strong in the up-time manner to wake me up and settle the head I had from too much wine the night before, I had a little bread and olive oil. Already the notes were turning in my head. Cramming the bread into my mouth, I went to the little piano in the room, and played. Thoughts, notes, melodies, flew through my head and down my arms into my fingers. Music filled the room. I saw Girolamo stick his head in the door, smile, and leave me to it.

I do not know how long I played, Father Thomas. It must have been hours, though, for when I looked up at one place, there was Elizabeth, sitting in a chair, listening.

"Hello," I said, stilling my hands. "How long have you been there? Why didn't you say something?"

"A while," she said, grinning at me, "and I didn't want to disturb you. It looked like good therapy."

I shrugged, and made notes again. "Just thinking, feeling. I am going to write a monument to Papa. A passion."

"Giacomo!" she exclaimed. "How wonderful! Do you have a theme yet?"

So practical, Elizabeth is. Of course, after working with me on the Lament for a Fallen Eagle, she has some idea of how I think.

"Actually, I have four." I played one as I sang without words

"That is the theme from your Lament," she nodded. "Appropriate."

Next I improvised against a melody she would know.

Elizabeth clapped her hands. "Oh, Giacomo, the theme from Bach's Passacaglia in C Minor! How beautiful. What's next?"

For the third one I just played, and I grinned as Elizabeth's eyes popped wide and her jaw did drop. "Giacomo, you wouldn't. Not You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling! Not in a passion."

"Why not? It's a good melody, and Papa always liked a joke."

She just shook her head, and I moved on to the last theme, which I improvised for some time.

When I stopped at the end, Elizabeth said nothing, just sat with her hands tightly folded together. I could see tears waiting to flow, so I pulled a handkerchief from my sleeve and handed it to her. She dabbed her eyes, and looked at me so solemn. "I don't know that one, but it was beautiful."

"You don't know it," I told her, "because it is new. I made it just today."

She nodded, and wiped her eyes again. "It is beautiful."

"So, I have two themes from the future, and two themes of my own from now. I think I am ready."

I turned again to my friend Father Athanasius Kircher, SJ, for the text. I had decided to use the same texts as the great Johann Sebastian Bach had used for his St. Matthew’s Passion in the future, but for Papa, I wanted the Latin, not the German. The good father was able to provide me a clean text of those passages in modern Latin in just a few days. He is Jesuit, after all; so to say he knows his Bible is like saying water is wet. It did not take him long.

You may be expecting, Father, to read of another epic marathon of music composing like when Lament for a Fallen Eagle was birthed. It did not happen that way. Yes, the writing of music does sometimes take that white-hot path through a forge. For example, the great oratorio Messiah, written a hundred years from now by one Georg Friederich Händel according to the up-timers, over three hours of music, was written in twenty-four days. Against that account, our labor—Elizabeth's and mine—in writing the Lament was fast but not fantastic.

But more often, the composer writes at a steady consistent pace, crafting his work well, but not wearing out his mind or facility in the doing of it—like a cooper shaping the staves of a barrel, carefully, so that they all fit together properly and serve their purpose. And so it was with this passion. I would teach during the day, and at night would sit with pencil in hand and scribe notes onto the staffs. There was no rush, no hurry this time; no deadline like there was with the Lament. I was doing this mostly for Papa and a little for me, so I cherished the writing of it. Sometimes I felt as if Papa, craftsman that he was, was standing beside me, watching the notes take form on the page.

I confess, though, Father, that the music flowed from my fingers. The various parts took shape with deliberate speed. Three nights a week, Elizabeth would come, and she and I would sing the newest lines for Girolamo and his workers, to their approval. Sometimes I would go back and revise, but mostly it was face forward and make new notes.

The death of my father still weighed on me, but did not weigh me down. The writing was a joy, the teaching was a joy, and from time to time Girolamo and Elizabeth would make the conspiracy to get me out of the house. One of their best tactics that I could not resist was to go to the garage sales, or go antiquing, as Elizabeth would say.

It is the custom of the native Grantvillers that they will from time to time cull their possessions. I know that must seem strange to you; outré, as those snooty Parisian clerics might say. But you would have to come to Grantville to understand just how much more material wealth even the more humble of the up-timers possesses than the average Roman. And it is almost a mania with them that they must have new "stuff" as they call it, so from time to time they will index their possessions, determine which items have been of little use or have become less attractive since the last time they did the exercise, gather the last items together, and then conduct a sale.

There are no laws about markets in Grantville, but the custom is that these sales occur on Fridays and Saturdays. They occur most often in late spring, summer, and early autumn, but even in other seasons they can happen if the weather is accommodating.

They may occur in a yard under a tree, in a structure by the home called a garage, or sometimes several people will combine and erect a large awning or rent a communal space for the purpose.

Sometimes they do it just to "clean house," as the up-timers put it, but sometimes they do it for to raise funds for communal support and for charities.

Of course, we down-timers are ravenous for up-time goods, so competition and bidding for objects can sometimes be quite fierce. The only thing that has prevented outright duels at times is that because these sales are often spontaneous, by the time word of the offerings has traveled to where the merchants are, the sales may be over. Even so, observing the activities at one of these can sometimes be as entertaining as watching a commedia all'improviso. More than once I had to cough or bite my cheek to stifle laughing as I watched pompous or rapacious Germans face off over what Elizabeth called a plastic "doo-dad."

I would very seldom buy anything. I am mindful of my temporary condition still, and my responsibilities to my patrons, so I dare not weigh myself down with additional baggage. And although I do have patronage, it is not remunerative enough for me to compete with angry burghers seeking the unique material goods of Grantville. Twice, however, I found items that I could not resist at times where no one seemed to want them but me.

The first was a garment, what the Grantvillers call a "t-shirt." Think of a simple shirt with short sleeves, only a round opening for the head, no placket. The material is light. I am told it is usually cotton, but it is a very fine knit, not woven. They come in all manner of colors, many of them very bright with the up-time dyes, and they often have some kind of picture or saying printed on them. The one that caught my eye that February day was a bright pink, of a color to remind me of roses in the garden of Cardinal Barberini, the younger of that name. That gathered my eye, yes, but the reason I bought it was for the picture on the front. It was a representation of the Piazza Navona in Roma. Oh, not identical to how it looked when I last walked there, but I could recognize it. When I saw it, the homesickness for Roma welled up in me, and I would have paid almost any price for it. Fortunately, Elizabeth took if from my clutching fingers and did as fine a job of bargaining as I have ever seen—although she was more civil about it than most in Roma would have been.

I try not to wear the shirt often, because it is irreplaceable, of course. I wonder, too, how it came to be in Grantville. The vendor did not know its ultimate provenance, only who she bought it from. But whenever the yearning for Roma grows too strong, I take the shirt out of the closet and wear it beneath my cassock or doublet. It comforts.

The other item I bought at a garage sale was a book. Rather, books; several volumes from the collected works of one François-Marie Arouet, known to up-time posterity as Voltaire. He was, as you see from the name, French, an up-timer of sorts, born in 1694 and dying some time much later. I might have bought them even if they had been in the original French language, but these were old books—maybe as much as seventy-five years from before the Ring of Fire—that had been translated into English. The vendor said that they had been found in a trunk that had belonged to her grandfather, and given her apparent aged condition, her grandfather could well have been alive when Voltaire set pen to paper to write the originals!

I bought them because I thought that reading something written much closer to our time would not strain my brain so much, but still give me practice with Grantville-style English. You yourself must admit, dear Father, that being an academician is not within my gifts. I will now pause, so that you may laugh.

This Voltaire was a man of letters, a letterato. He wrote almost every kind of writing, and much of it. A lifetime's writing for the man took up many many volumes, and I was and am sad that I was only able to find three at this sale. I do not agree with everything in his writings, but he makes me think.

One volume was essays, one was history, but the third, it was a thing most special. It contained dramas by the man. And they were good enough that I wish I could have found his poetry as well.

So in the evening, after I did the day's work on the passion, I would read something from Voltaire, and the dramas, they spoke to me. Particularly the one called Brutus. But then, you would have expected that, of course. I am a man of Roma, after all.

It is a lengthy work, and how it presents Brutus is perhaps different from our assumptions, but it made me think. It made me think for a long time, while I was writing the passion.

When February was close to end, I was also close to finishing the passion. I was writing the music for the crucifixion, you see, using as my theme the gloriousness of the Bach Passacaglia in C Minor I had played for Elizabeth. For her and for Girolamo I played as much I had written at one evening, singing parts as I did so, skipping from voice to voice. I thought it comedic, almost like the commedia, but they were not smiling when I stopped my hands playing. Elizabeth was dabbing at her eyes with another of my handkerchiefs, and Girolamo, the man of many words, did nod slowly.

"Tell me, Giacomo," he said. "If this is a passion and not a mass, why do I hear the Dies Irae in what you played?"

"My friend, was that not a Day of Wrath? Was it not a Day of Judgment?" I replied. He nodded again. "Then what better second theme for this section than the Dies Irae?"

He waved his hand, and said with a smile, "You don't tell me how to shape wood. I cannot tell you how to shape notes."

I looked to Elizabeth. She was quiet. I guess the music it made her sad. But she said, "It's beautiful, Giacomo. Simply beautiful."

"You are almost finished, yes?" Girolamo asked.

"Yes." I said.

"So, what will you do next? I know you," he said with look of sternness on his face, perhaps a mask, perhaps not so much. "If you have no major work before you, you get moody."

"Moody?" I was astounded that he would say such. "Me?"

"Yes, you."

Elizabeth was smiling, which I liked after seeing her sad. "Yes, what will you do next?" she said.

I shrugged. "I am thinking about an opera," I said.

That took both of them by surprise. I grinned at them.

"Seriously?" Elizabeth asked.

"Seriously."

"What about?" Girolamo asked. "What text?"

So I spent the next hour or so describing to them the story of Brutus as told by Voltaire's tragedy, all the characters, and the plot, and all the outs and ins. I was quite dry by the time I finished that, and went in search of wine. When I returned to the room, Girolamo looked at me, and said, "Do it. You know you want to. I would tell you to make it great, to make it bellisima, but I will not waste my breath. You will do it anyway." He grinned at me.

"Yes," Elizabeth agreed. "Do it."

And so it was decided.

February became March. It was slightly warmer outside, which, man of Roma that I am, I was very grateful for. And I was almost done with the passion, writing the final section, the Resurrection, with the following Alleluia Amen. It was going well. I would be done very soon. But I was not happy. I could not think of a poet to make the libretto from Voltaire's play, and no one I asked in the high school had any ideas. I tried not to think about it, but you know how I am. If I can worry, I will.

Father Athanasius had long since let the cat out of the musical bag, as some Grantvillers might put it, and told David Brady at St Mary's church what I was working on. He had been practically begging me to come by the church and play him what I had written, so the first Saturday in March I met him at the church and played him what I had notated, singing the parts where I could.

"Gia-Gia-Giacomo," he stuttered when I was done, "that is great stuff! I would love to have our choir perform it for Easter next month. How soon can I get the voice parts?"

This did take me off my balance, I must say. All along my mind had been that I was doing it for my Papa. I meant to have it performed at some time, but never did I think it would happen this fast. But, I thought, my Papa would like to hear it, too, even if he is in Heaven. I turned to David. "If you have someone who can copy the parts, as soon as they are done. I only have one last chorus to finish, it may all be written by tomorrow night."

"Wonderful!" David rubbed his hands together, so very like some Roman merchant who scents an easy fish coming into his net. "There are several high school students who have been helping Thomas Schwarzberg copy music down from the records and CDs. I'll get some of them over here tomorrow." Then he stopped rubbing his hands and looked worried. "But what about instrumental parts?"

"I will do those," I promised. "And none of them will be hard."

David looked relieved at that. We talked a little more about the music, and about calling rehearsals. When we were done, I turned to go, and there was Father A standing in the doorway behind me, arms crossed, smiling.

"So, Giacomo, we are going to be blessed by some new music from you, I understand."

"Well, Father," I said, "since you were the one who told David about it, then you are at least responsible for this in part."

He nodded, with one of those smooth Jesuit smiles.

As I walked by, he stepped into place beside me. "I hear that you may be considering doing something new."

"Talked to Elizabeth, have you?" I said. Another one of those Jesuit smiles came back at me. "Yes, I am thinking about an opera."

"Have you started?"

"No."

"Why not?"

"Because I can't find a poet to do the libretto," I said in frustration, "and I cannot even think of the themes to base the work on until I see the libretto."

"So, do you want to do it in French, Italian, English, or German?" Father A asked.

I stopped and looked at him. After a moment, I shook my head as I remembered who I was speaking with, and replied, "I suppose I never considered that. But I am in Grantville, which is in Germany, and the patrons will be German, so I guess that German would be best."

He shrugged. "I can do it."

We started walking again. I said, "Pardon me, Father, but do you have time?"

Father A laughed. "I have as much time as I want, actually. The parish runs well, the order of service for the year is laid out, and barring sudden emergencies I can spend some time doing something like this to help a friend."

"Okay, then," I said. "I want to base the opera on a play by Voltaire, an up-time French writer."

"Which one?" Father A asked.

"Brutus. I have a copy in English . . . "

Father A interrupted before I could finish the sentence saying, "I've read the original in French. The high school up-time French teacher has some books for the students of French language, and one of them has several plays. It was . . . interesting."

"Oh. Well." Once again Father A had managed to reduce me to words of one syllable without even really trying. A Jesuit of Jesuits, I tell you.

"So," the good father looked at me, "when do you want to see a first draft of the libretto?"

"Um," now I couldn't even form words. I forced myself to think, and came back with, "When is Easter this year?"

"April 16th." Father A responded.

"Then on April 20th," I said. "I will be busy with this performance of the passion until not long before then."

"Good," Father A said. "I will have it for you then."

He nodded, turned and walked off. I watched him go, realizing that once again I had been hooked by that wily Jesuit for something. I didn't know what, for sure, but he had something in mind. I was certain.

So now my life got very busy again. I was right; it took me only one more evening to finish the final chorus. I could hear it in my head so clear, so it was just a matter of writing it down, and between myself and Elizabeth it did not take long. And Elizabeth had been coming in every couple of days to make a clean final copy of the passion, so the students that David Brady paid to copy the parts to make the mimeographs were able to get started and I still had my original copy to make the instrument parts.

That did not take me long. I decided make the parts simple: organ, piano, two flutes, and just because it would have made my Papa smile, a guitar.

To use another Grantville phrase, Father, guitars in Grantville are a whole different breed of cat than the guitarras or vihuelas you have seen in Roma. They are very mature instruments from the up-time, larger, with greater sound and resonance than all but the very finest lutes. A guitar well-played is a master's instrument, and we are fortunate that in Grantville there is indeed a master of the instrument, Signor Atwood Cochran. He is a colleague of Master Weller, a teacher of music now and in the up-time before the Ring of Fire happened, but in his youth and early middle years he was a professional performer with guitar. He agreed to play for the passion performance when I asked, so I wrote a part of some skill for him.

Rehearsals began in the last week of March. I still had some instrument parts to finish, but enough was ready that we could begin, and I would have the final parts done before we got to those sections of the passion.

As with any new work, the choir struggled at first to learn it. The Latin was also a bit difficult for some of the up-timer singers, since they have used the vernacular languages for the church services most of their lives. They are not professionals, to know Latin, and they are not used to having new music every week, but they have a heart for the music, and once they learn their parts, they are good. And we had time. So I was not worried.

I played the organ. The church's regular musician played the piano. Two girls from the high school band played the flutes. And Master Atwood played the guitar. It was good.

By the beginning of April the rehearsals were going better. And it was a good thing that they were, because God decided to make my life a bit more complicated. Deo Gratias. Seriously. Because early in April I looked up from my desk one afternoon after classes at the high school to see a distinguished older German walking into my classroom. It was Master Heinrich Schütz, Father Thomas! Even you in Roma know that name, I believe. Perhaps il primo musician north of the Alps, a man who studied with Gabrieli and Monteverdi, a man who corresponds with the finest musicians in the world, come to Grantville, walking into my classroom.

I think I did not babble. Neither he nor his companion acted as if I did. So I believe I made a good first impression. I had corresponded with the man in the past, as had most musicians of note. But to actually meet him in the flesh—to have him come to me—was staggering to me.

His purpose in coming was the same as mine, mostly—to learn as much as he could about the music from the future, and to learn about Grantville. We had many discussions over the next few weeks, and we listened to much music together. But needless to say this was a very serious distraction to me, and I really had to bear down on myself to focus during rehearsals.

As you would expect, I did invite Master Schütz to come to the performance of the passion. David had scheduled it to be performed twice: once on Good Friday, and once on Easter morning. I hoped he would be there, because I valued his opinion immensely. But at the same time, the pressure it was now on me. I confess I started having some trouble sleeping.

The rehearsals, however, continued to go well, but it felt like the butterflies in my stomach had teeth. I survived; however, the stock of wine at Casa Zenti e Carissimi was beginning to lower alarmingly.

It was good that the rehearsals went smooth, because life outside the church was still interesting, in much the same way that the Book of Ecclesiastes is interesting. Master Schütz, within days of arriving, had a crisis when Master Weller and the high school brass played a piece of music written by him in 1647. Yes, that is correct Father Thomas, the year 1647—from thirteen years in the future.

Poor Master Schütz for a few days had a fever of the mind, I think. His assistant, a young man named Lukas Amsel, finally had to bring a Lutheran pastor named Johann Rothmaler to come visit and soothe his spirits, which the good pastor, heretic though the Church may proclaim him to be, accomplished.

But that episode caused me to do something I had not done in all the time I had been in Grantville. I went to the library and looked for information about me. Not for pride's sake, Father. I am not likely to get the big head in Grantville. A look around at everything that has come after me, and a history that did not well regard me, has permanently shrunk my pride, I believe. No, it is that I was concerned that if Master Schütz, that good man, could become unsound of mind from knowing about his future, I was under the same risk. Perhaps it was foolhardy of me to do it just before the big performance, but I wanted to know. Lack of patience is a human error, good Father, as you well know. I am, at times, all too human—as you also know.

It contained nothing that surprised me, after all—except for one thing. No, two. I had my career as a musician in Roma, developing some repute. I eventually entered holy orders, which I think will surprise you not. Some small portion of my music survived to the up-time future, though not as much as of Master Schütz's works. I was apparently renowned more for being a teacher than a composer to the future.

But I said two things surprised. One, it seems that in the world that Grantville came from, Princess Kristina, daughter of Gustavus Adolphus, became queen of Sweden after her father's death, but when she became a woman full-grown, she had much difficulty with the nobles of Sweden. She eventually abdicated, moved to Roma, and became a Catholic. That's one thing, and I leave it to you, Father Thomas, as to whether this should be made known to the Holy Father and his college of cardinals. Of course, bear in mind, that if we know this, undoubtedly the redoubtable Gustavus Adolphus also knows it by now, so I have some doubt as to whether anything can be made of this information. As the Grantvillers would say with another of their innumerable sayings, "The butterfly has flapped its wings." It is a very odd way to say that the arrival of Grantville has changed the future that would have been, but then Grantville can seem very odd at times.

The second thing that surprised is after Queen Kristina's abdication, conversion, and removal to Roma, it seems that at some point the queen's path crossed mine, for we apparently had an extended relationship until her death. The records I read were not clear as to the exact nature or content of that relationship, but even if it were spiritual only, it was apparently both warm and deep.

The second thing that surprised is after Queen Kristina's abdication, conversion, and removal to Roma, it seems that at some point the queen's path crossed mine, for we apparently had an extended relationship until her death. The records I read were not clear as to the exact nature or content of that relationship, but even if it were spiritual only, it was apparently both warm and deep.

That rocked me back on the heels of my shoes, Father Thomas. And when I was not practicing, or worrying about Master Schütz, I wondered about that. And the stock of wine at Casa Zenti e Carissimi lowered even faster. Girolamo muttered about it, but I ignored him.

After his conversation with Pastor Rothmaler, Master Schütz returned to his normal self very quick. And it seemed I was spending every waking moment but for my time at the school at the church working with David and the other musicians. Progress was being made, and I had not a doubt that we would be ready. But always in the back of my mind was the princess, and I at last did something perhaps foolish—I wrote her a letter, to the palace in Magdeburg, explaining who I was, that although we had never met, we had a connection in the up-timers' future, and inviting her to come to Grantville to hear the passion. And then I forgot about it, for never I thought she would come.

Good Friday came, and we were ready. I will not bore you with trying to describe a performance of three-quarters of an hour of music, but I will say that it went, if not perfectly, then very well. The soprano and tenor soloists were very good, the alto was almost their match, and the bass/baritone, although having a thin voice, was still adequate for his part. I have seen performances in Roma with less quality.

The girls on flute were amazingly good, but Master Atwood, ah, he was superb. I believe I have mentioned before that St. Mary's church is not a large building, certainly not on the scale of a basilica or cathedral. But from where he was sitting on the platform in the apse, his guitar could be heard at the rear of the nave, and his part was not simple. He played to perfection. Deo Gratias for that as well.

The choir, though not large, sang with heart and feeling, and in the end, if they were not perfect, I doubt that anyone in the nave noticed.

So at the end of the service, after Father Athanasius had blessed and released everyone, there was much congratulations and praises and slapping of backs from those who had listened. Performers and audience were all smiles. Master Schütz had come, and was most kind in his remarks. Two of the audience complimented me on the use of the Bach theme, and at least three different times people edged up to me and whispered, "Did I really hear You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling in this?"

As I stood grinning after that third exchange, I felt a tug on my breeches. I looked down to see young Leah, Elizabeth's daughter, with her smiling mother standing behind her. She is six, and is a very proper young lady. I went to one knee before her.

"Good evening, my gnappetta. What can I do for you?"

"Mr. Giacomo," she began, "that was very pretty."

"Why, thank you, dear one," I replied, giving her a quick hug.

"But it was too long."

Elizabeth gasped. "Leah! That was rude!"

I chuckled as I stood up, and said, "But she is right, for a child. I had much the same thought as a young choir boy."

Elizabeth looked back at me, and grinned. "I have trouble seeing you as a choirboy, Jude." Yes, she still used her nickname for me. "But I bet you were a bit of a rascal, though."

"Not a bit," I answered. "According to my choir masters, I was an imp in boy's skin, and I would come to no good end."

"Then it is good that they were wrong."

Most of the people had moved away from us toward the doors to the narthex. Elizabeth's children, Leah and her older brother Daniel were playing on the platform. I looked at Elizabeth, and realized, as if for the first time, that she had been my muse—my very Euterpe—since I had first arrived in Grantville. I would not be where I was without her. I would not have accomplished the things I had done without her. And without a doubt, I would not have written the music I had written without her.

Most of the people had moved away from us toward the doors to the narthex. Elizabeth's children, Leah and her older brother Daniel were playing on the platform. I looked at Elizabeth, and realized, as if for the first time, that she had been my muse—my very Euterpe—since I had first arrived in Grantville. I would not be where I was without her. I would not have accomplished the things I had done without her. And without a doubt, I would not have written the music I had written without her.

This flashed through my mind, and seemed to flash through my body as well, leaving all with a tingle like when your foot is asleep and starts to wake up.

I looked at her, saying nothing. The smile had long slipped off of my face. Now all I could do was stare into her eyes.

Elizabeth's smile faded and slipped away itself. She looked into my eyes. I wondered if she was feeling what I was feeling.

I raised a hand, and with my finger traced the line of her cheekbone. She closed her eyes, and just for a moment seemed to lean toward me.

"Mommy!"

Elizabeth's eyes snapped open at the wail from Leah, and she spun from me to go rescue her child from her perch hanging from the edge of the organ loft. I could not see how the little one could have even reached it, but reach it she had. Elizabeth brought her down, holding one hand securely, then snapped her fingers for Daniel to take the other one. For an eight-year-old boy, he had sufficient sense not to argue with her just then.

She started to lead her children down the aisle to the narthex. I stepped forward.

"Elizabeth . . . "

I didn't know what to say.

She stopped.

"Don't, Giacomo. Just . . . don't."

They left together. And me—I had the taste of ashes in my mouth. I walked up on the platform, sat down in one of the instrumentalist's chairs, and put my head in my hands.

I don't know how long I sat there. Long enough for everyone to leave, and most of the lights were turned out. Then I felt more than heard someone settle in a chair next to me. I knew who it was before I ever looked up.

"Bless me, Father, for I have sinned.'

Father A looked back at me. Did I mention he has that Jesuit stare, the one that can look through solid stone walls and through locked doors to see truth? Well he does, Father Thomas. It's every bit as good as yours.

"In what way, Giacomo?"

I skipped the usual responses about Christ knowing all things and when my last confession was.

"Tonight, Father, just a few minutes ago, I may have committed adultery in my mind with a married woman."

Father A pursed his lips, then after a few seconds, said, "Mrs. Jordan?"

I nodded, and put my head back in my hands.

We sat in silence for some while. Finally he stirred, leaning forward to clasp his hands before him and place his elbows on his knees.

"Do you repent of your thoughts and action? Are you feeling contrition?"

"I am sorry that I showed her how I felt," I said, dropping my hands. "I am sorry that I touched her face. I am sorry that I may have killed our friendship. I am sorry that she may now avoid me. But I am not sorry that I feel what I feel for her. She is worthy of that, and more."

"Mmm." Father A stared at the floor. Finally, he looked over at me. "At least you have not acted upon those feelings. Lust is a sin; temptation is not. Will you accept penance from me?"

"Yes, Father."

"Good. Then your penance will be to write new settings for the Pater Noster, for the Magnificat, and for the Nunc Dimittis. Next week, before you begin the Brutus. And," he held up his hand, "you will treat Mrs. Jordan with the same respect and care you would reserve for your own sisters. She is your sister, not Fred Jordan's wife."

"That . . . will be hard," I said after a moment. "But I will do it."

"Good," Father A repeated. Then he closed the confession with, "Deinde, ego te absolvo a peccatis tuis in nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti. Amen."He traced a cross over me, then set a hand on my head. "Come, Giacomo. Let me walk you home."

Father A was never one to let ritual get in the way of substance, I would say. Plus, he has been living among up-timers for quite some time, remember, and has absorbed some of their "cut through the red tape" attitude, I think.

He said nothing more. We walked all the way to my house in silence. When we got there, I said, "Thank you, Father."

"Get some sleep, Giacomo. I will see you on Sunday."

He watched as I walked up the steps and entered the house.

I closed the door behind me. The house was dark. Girolamo and his workers were not here. Probably at the Thuringen Gardens, I thought. I poured myself a glass of wine, took one sip, then put it down. It was not what I wanted. Finally, not knowing what else to do, I went to bed. I lay awake for hours, but finally did sleep.

I know, dear Father Thomas, that I have disappointed you with this recounting. But the story is not done yet. Bear with me some while longer, please, for the love you have for me.

That Saturday, I was in a fog. My mind was as turgid as the waters of the Tiber by the Ponte Sant'Angelo in August. Girolamo spoke to me several times, but gave up on conversation after a while. Late in the afternoon, I seemed to wake up, enough so that I began sketching ideas for the Pater Noster that Father A required of me.

When I finally went to bed, I remember no dreams.

I awoke to see the sun rising on Sunday morning, almost the same Giacomo. I ate a little bread and olive oil, drank a very little wine, checked my clothes for spots, and headed for St. Mary's.

I arrived just as Father A was completing the early Mass, done in Latin for those who like that. I slipped in the back and took a seat in an empty pew.

I like watching Father A as a celebrant. He believes what he is saying, he believes in what he is doing, and that brings peace to all who are there.

That Sunday, after the Mass had concluded and the parishioners had left, I wandered up to the platform and sat at the organ. I began playing, softly, quietly. There is such a thing as muscle memory. My hands played, moving from position to position without my mind thinking of it. Themes began occurring to me, and poured from my mind to my fingers.

I think it was close to an hour before I brought the playing to the final cadence. I took my hands from the keys, realizing as I did so that the three settings that Father A had directed me to write were in my mind—complete, entire. I had written them; all I needed to do was write them down.

A noise crossed my ear, and I looked up to see Father A moving chairs around on the platform. A quick glance at the clock told me that we needed to get things ready for the noon mass and the performance of the passion.

I stepped down from the organ and began moving chairs too.

"Father," I asked. "Is there some reason you are doing this, instead of the sexton?"

"Giacomo," Father A replied with a grunt as he lifted a chair over a rail, "a pastor in a small church needs to be flexible, be willing to do what is needed. After all, if it was not beneath the dignity of Christ to wash the feet of his disciples, it cannot be beneath my dignity to sweep a floor, empty the trash, or in this case, move some furniture."

So you see why I like Father A. He is like a hand wearing a well-fitted glove—a good man being a good priest. You know, Father Thomas, that such is not always the case.

With two of us, it took only a few more minutes to have the places ready for the instruments. Father A straightened up and dusted his hands together.

"That's ready," he said. Then he looked over at me with his head tilted to one side a bit, and said, "Are you ready, Giacomo?"

I knew he was asking about more than the music. "Yes, Father, I am."

He nodded, and turned to open the lid of the piano. Musicians began arriving at that moment, and in a few minutes David Brady was tuning the instruments and leading the choir in vocalises to warm their cold voices. I took my place at the organ, and waited.

The Sunday performance was perhaps even better than the Friday performance. The soloists in particular were more relaxed, and it could be heard in their voices. Both Signora Marla Linder and Signor Andrea Abati, two of the best voices I have ever heard, had returned to Magdeburg some time ago, so I knew they would not be available and wrote the soprano parts accordingly. In the second performance, those parts were realized almost perfectly. I could not help but smile as I accompanied.

After we were done, there was even more congratulations and comments (and whispers about You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling) than on Friday. I smiled and joked with everyone, particularly Girolamo, but inside I felt a bit hollow. I had not expected Elizabeth to attend—she has responsibilities at her Presbyterian church on Sunday mornings—but it still felt hurting when she wasn't there when I looked out at the parishioners.

As I stood with Girolamo, trading Easter greetings and the occasional Easter joke in Italian, Father Athanasius appeared at my elbow.

"Giacomo, come with me."

He took my arm and pulled me away from Girolamo, heading for his office.

"What is it, Father?" I asked after a few steps

"You'll see."

Before I could respond to his Jesuit terseness, we arrived at his office. He dragged me through the doorway, and closed it behind us.

In his office, seated in a chair, was a young girl, looking to be about Daniel's age. She was sitting straight, forearms laid along the chair arms, feet swinging gently. Her hair was long, dark, and somewhat curly. Her eyes were bright and lively. I would have called her pretty, but for her nose. Quite strong, that nose was, and difficult to overlook.

There were two women standing behind her chair; up-timers by their dress. Nothing too unusual about that, except that I knew one of them slightly. It was Lady Beth Haygood, an up-timer who was one of Mary Simpson's aides and assistants and who had moved to Magdeburg from Grantville recently. Lady is, in her case, not a title, but part of her name. Everyone calls her Ladybeth, like it is one word.

My first clue that the girl was more than just a little girl was the two very large and very strong men also in the room. One stood behind her chair with the women, the other stood by the door.

I looked to Father A with questions in my eyes.

"Giacomo Carissimi," he began with another of those Jesuit smiles, "I have the privilege of presenting you to Princess Kristina of Sweden, daughter of Gustavus Adolphus." He nodded toward the girl.

I froze for a moment, caught very much off the guard. I was beginning to really dislike that Jesuit smile.

I turned to face the princess, and gave her a deep bow, slow and serious. I did not genuflect, of course, as she was neither my bishop nor my sovereign.

After I straightened from the bow, I said, "I am very pleased to meet you, Your Highness." And a thought came to me that the very large men must be her guards. I reminded myself to behave.

The princess nodded back to me, then looked up at Lady Beth. Funny, I did not expect up-timers to be serving as ladies in waiting to the princess.

"Good afternoon, Master Carissimi," Lady Beth began. "Princess Kristina has been informed that you are a noted author, composer, and teacher."

"I hesitate to use 'noted,' " I replied, "but I have some small reputation, particularly back in Roma."

Princess Kristina stood, and held out her hand in the Grantville manner. I quickly looked at Father A and the women. The other woman nodded, so I took her hand in mine and shook it gently.

"I am pleased to meet you, Master Carissimi," the princess said carefully. "I saw your friend Master Zenti in December in Magdeburg. It was good to see him again."

"Again, Your Highness?" I did not know that he had known the princess before then.

"He lived in Stockholm a few years ago, making harpsichords and other instruments. He made a very nice harpsichord for my mother, but she won't let me play it."

The princess sounded much like every other young girl in the world who chafes a bit at her mother's hands. I smiled at that. But the knowledge that Girolamo had spent time in Sweden was new to me. I had not heard that before. I would have to kid him about that later.

The princess picked up a paper from the top of the desk before her.

"I got your letter," she said. "I understand that we knew one another in the future." Her sober expression melted into a wide grin. "It sounds so funny to say that, you know. Frau Caroline," she looked back at the woman who hadn't spoken, "says that verbs can't deal with Grantville. But," the princess looked back at me, "you sounded like a nice man, and I wanted to meet you. And I like music, so I wanted to hear your Passion According to Saint Matthew, so when Frau Lady Beth," she nodded toward the other woman, "said she had to come back to Grantville for some business for this weekend, I begged as prettily as I knew how that she let me come with her. She said yes, so here I am to say thank you."

The princess smiled again, transforming her plain face, while Frau Caroline gave a lady-like snort, and said, "No, you did not beg prettily. You were a royal pain in the posterior until Lady Beth agreed."

I had to cough to stifle the laugh that almost erupted from me at the joke.

"Master Giacomo," Frau Lady Beth said, "you might remember that I work with and for Frau Mary Simpson on many projects."

I nodded, but said nothing, wondering where she would go with this approach.

"Frau Simpson knows of you from the up-time histories, and esteems you and your work. She has left Magdeburg on a trip, but she left instructions that I approach you about a position."

Now I am very awake, my ears almost trembling they want to hear so badly. A position—magic words to any musician.

"Frau Simpson has enlisted sufficient sponsors and support to establish a Royal Academy of Music in Magdeburg."

Frau Lady Beth stopped, and after a moment, prodded Princess Kristina with a fingertip. The princess sat up very straight, and said, "The royal family of Sweden offers you the position of Master and Director of the Royal Academy of Music, for a salary to be set later."

I was stunned. I did not move, not until Father A stirred beside me. Then I closed my mouth, to look less than the country rube I am afraid I appeared, and swallowed.

"Th-thank you, your highness," I stammered, and bowed again. "I am very, very much honored by what you say, and I very much want to take the position. But . . . "

"But?" Frau Lady Beth asked.

"But I am in Grantville under the sponsorship of people in Roma. I cannot take this new position without seeking at least their understanding, even their permission. I will write to them tomorrow, and get a message back as quickly as I can. If they agree, then I am your man. But if you must have an answer today, then it is no. I cannot break my word to those who have supported me for a year."

"Hmm," Frau Lady Beth said. "Tell you what; let's say that's a qualified yes. We won't look for another candidate until you have an answer, but if you haven't heard in three months, we reserve the right to begin looking again."

I nodded yes as fast as I could move my head, Father Thomas. The position of a lifetime, this was! I wanted it so badly even my toenails ached with desire.

"Good." Frau Lady Beth looked satisfied. "And one more thing. We are going to build an opera house in Magdeburg. The first one anywhere in the world. Do you write operas, Master Giacomo?"

Father A coughed beside me, and I knew he was trying not to laugh. I fear his Jesuit self-control almost slipped.

"I have," I responded, "and by coincidence I am about to begin writing another."

Frau Lady Beth's eyebrows arched, then she said, "Well, let us kill two birds with one stone then. Can you accept a commission to write an opera without consulting your people in Rome?"

I nodded, not trusting my voice.

"Good. Then tomorrow morning, let us discuss that."

It seemed that those words ended the meeting, for the princess stood up and shook my hand again, and then she and her ladies and guards left the room. My eyes must have been very wide when I looked at Father A, because he began to laugh. It took him a while to stop.

"Ah, Giacomo, if you could only have seen your face earlier." He chuckled for just a moment, then went serious again. "I recognize the opportunity this provides you, and I am glad that it has come to you while you are young enough to really enjoy it. Bring me your letter tomorrow, and I will see that it gets to Rome quickly. Two weeks for an answer," he said. "Maybe a bit more."

You Jesuits and your message system. But this time it would work for me, so all I could say was, "Thank you, Father."

So we went back out into the nave to mingle with the people that were still talking. I walked through the door in time to see Girolamo make a most elegant bow to the princess. The man does know how to bow. Maybe I should take lessons from him.

The princess left after a few minutes of talking to Girolamo. That seemed to be what everyone else was waiting for to leave, because after five more minutes, they were all gone, even Girolamo. Just me and Father A left in the nave.

I was excited. My breath was coming fast. But I took the time to gather my music and my notes and put them in my folder. With that tucked under my arm, I looked at Father A.

"A good day, Giacomo," he said with a smile—an honest one, not that Jesuit smile. "You have a marvelous future in front of you. Good luck! Bring me your letter tomorrow. And don't forget your penance."

I grinned back at him. "I will have those done by the end of the week, Father. I will see you tomorrow."

He shook hands with me, and I left.

I whistled most of the way home; the melody and theme from Bach's Contrapunctus V from The Art of Fugue, if I remember right. I felt like I was walking on clouds, like my feet were not touching ground. And then I turned up the sidewalk to our house.

I was three steps from the front door when it crashed into my mind. To take the position, I would have to move to Magdeburg.

Elizabeth.

Dio in Cielo!

God in Heaven indeed. The chance of a lifetime, and I had to abandon my muse to grasp it. I knew without asking that she would not move to Magdeburg, not leave her friends and family and husband. Even though he was gone a lot doing diplomatic things, still, Grantville was their home.

The sun was shining on that cool spring day. It was maybe an hour past noon. It felt like three hours past midnight. I was dark in my soul.

It took time to walk three steps to the door and go into the house. I went to the kitchen, filled a pitcher from one of the few small barrels of wine we had left, opened it, and drank it quickly, without tasting the liquid going down my throat. Sitting at the kitchen table, I stared at the sink, and drank.

Two, maybe three pitchers later—I don't remember so clearly—Girolamo came in and found me weeping. He sighed, and put me to bed. I remember nothing before the next morning.

I woke up with a cheap wine hangover. Oh, very bad my head hurt. Like beating of the big kettle-drums, the tympani, in the high school band room, it felt. I was ready to shoot the cat that chased the mouse that died into my mouth. But four of the little blue pills which I know you know of by now, a little bread and olive oil, and two grande cups of dark strong bitter coffee, and I merely felt half-dead instead of three days in the grave. Girolamo smirked at me, but at least he made no jokes about me being a modern resurrection.

I stumbled out of the house and made my way to the school, where I found a note that Lady Beth Haygood would meet with me over my lunch break. And true to her word, she was at my classroom door at the moment the class ended.

I recalled Frau Lady Beth as being sharp, quick, and prepared. My memory was proved right. She came with ideas, with suggestions, and with a written contract for the commission of the Brutus. I suggested two small changes, she made them, we initialed those places, signed the contract. At that moment the hangover left me, and I felt good. To know that the opera was supported was great feeling to me.

And almost as good was when she handed me a check for one thousand USE dollars as the binding money for commission. I was to receive two thousand more when I deliver the completed opera to Frau Simpson or to Lady Beth.

Business concluded, she left. Not one to let dust gather on her shoes, was Lady Beth, just as I remembered.

After school that day I delivered to Father Athanasius the letter that I had written. I had not bothered to seal it. If it was going by the hands of the Jesuits, no seal on earth would prevent them from reading it if they wanted to.

The letter was addressed to Maestro Stefano Landi, the great musician and composer most beloved of the Barberini family, who supported me and was the intermediary between myself and other supporters. Maestro Landi had very carefully not identified who those other supporters were. My guess is it was the Barberini family, probably Cardinals Francesco and Antonio. Shrewd men with long vision. But it was to Maestro Landi I wrote for approval to take the post and move to Magdeburg.

Father A glanced at the letter. I am certain that he read it entire in but a moment. Then he folded it and laid it on his desk.

"Very good, Giacomo. I will see to it leaving as soon as may be." He peered at me. "Too much celebration last night, Giacomo?"

"No." I didn't want to talk about it.

"Ah." He nodded. "You realized, then. I knew you would, but not when." He shook his head, and said, "It will be best, Giacomo."

I nodded, but not certain in my heart of his rightness.

And now I entered a time of aloneness. I taught at the school, I went to mass on Sundays, elsewise I was at home.

At first I used the excuse that I needed to write the new settings I had promised Father A for my penance. In truth, it took me longer to write them than I had first thought. Nine days it took me, instead of a week. But the tenth day came, I gave them to Father A for copying, and he gave me the libretto for the Brutus.

I read through it straight that night. So strong it was, it lifted me out of my chair and forced me to walk about, reading parts of it out loud. Following his habit, Girolamo looked in on me, grinned, and went back to his workshop. But as I read, as I recited, as I projected the words, the musical shape of the opera began to form in my mind. By the end of the evening, I knew what I would do. Oh, not in every little petty detail, Father. But I knew the shape, the arc of the music, the themes I would use. And as with the passion, I knew that it would not take days or weeks to write the Brutus, but months. I guessed at three hours of music, which would be much work. Two, maybe three, maybe into four months to write it. But I was like a general facing to prepare a siege; I knew it would be work, but I knew I would win. And so it proved.

To you I must be honest, Father Thomas. It was not just the music that kept me in the house. It was also my cowardice. I did not want to see Elizabeth. For as long as I did not see her, I could tell my deluded self that things were okay between us.

And so April passed, with me not much better than an anchorite in a cloistered cell. Once I did go out in a night, the night of the day that Girolamo and his journeyman Johannes Fichtold and the apprentices all went to the Thuringen Gardens to celebrate the completion of the first piano created and crafted by Zenti & Associates. It was a piano of the size called grand, Father; beautiful, larger than the harpsichord I had seen in Girolamo's studio in Roma, housed in a darker wood—walnut, I believe—gleaming with varnish and with a painting on the inner lid that was much more respectable than the nymphs and satyrs on the earlier work. This one was of the gospel story of Christ calming the wind and waves, and one could almost feel the breath of wind when one sees it.

The piano was for the Count of Rudolstadt. That very day Girolamo had pronounced the varnish dry enough to consider moving it. So a message was sent to the castle, and that evening he and Johannes dragged me to the Gardens, protest though I did.

As fate would have it, the evening passed peaceably, though loudly, and I arrived back at Casa Zenti e Carissimi late that evening untouched, unharrowed, and unsober. No, Father, I had not become a drunkard. At least, not yet.

As soon as the piano was delivered, Girolamo left to tour neighboring cities. He did this with some frequency, looking for suppliers of materials for the work, and also looking for customers of the pianos. "Drumming up business," he repeated the Grantville phrase as he left. Me, I think he just liked to see new places. Plus, he visited the Freedom Arches everywhere he went.

After that I returned to my cloister, writing notes until late every evening, going to school in the morning, and drinking wine to go to sleep.

April turned to May.

The Americans have so many sayings. You have heard me quote them often enough in my letters. Here is another one: it never rains but it pours.

Two days after Girolamo left, I turned around in my classroom after the last class, and there was Father A standing in the doorway, holding a packet. He walked over and handed it to me. "It's addressed to you. From Roma."

So. The response had come. The butterflies with fangs woke up in my stomach and started chewing again. I broke the seal—ha! What a waste that was in a letter sent by the Jesuit couriers—and unfolded the outer covering to find another folded paper inside. Unfolding that, I found the response. Maestro Landi's command of language is as florid as his attire, but by the time of reaching the bottom, I was smiling.

"Good news?" Father A asked.

"I have permission to go to Magdeburg," I replied simply, handing him the letter so he could read for himself.

"That's good," he said, handing me back the letter. "So when do you think you'll go?"

And that thought, Father Thomas, brought me up short, like my Papa's hand on my collar when I was little. I had to decide. No more ifs or maybes. No more swinging in the wind. I had to decide. So I did.

"I will stay through the end of the school term," I said. I had to swallow before I could say the next words. "Then I will go to Magdeburg."

Father A nodded. "So, what, two weeks or so?"

"About that," I said.

"Good," was his reply. He clapped me on the shoulder, and left.

Funny, Father Thomas, but when it came down to it, it wasn't so hard to make the decision, I guess because of all the pain I had felt before.

I packed up my papers and stopped by the school office to tell the principal that I would be leaving at the end of the term. Then I went to the telegraph office to send a telegram to Frau Haygood telling her that I would definitely take the position, that I would be in Magdeburg by early June, and that we needed to talk about salary now. Then I went home and drank most of a pitcher of wine.

Two days later—I think it was a Friday—the school day was over, and I was clearing away my desk, packing some things up to take back to the house. I heard a noise, and looked up to see Elizabeth coming in the door. She stopped. I stood and came out from behind the desk. We stared at each other for a long time.

"So, when were you going to tell me?" she finally asked.

I did not try to pretend that I did not know what she meant. I shrugged. "Tomorrow, I thought."

She walked over and sat down in one of the student desks. I leaned back against my desk.

"Master of the Royal Academy of Music, huh? That sounds like a great gig." Her voice was light, but her eyes were not.

"I think it will be," I responded.

There was another period of long silence. I looked at her, drinking the lines of her hair, her face, her hands.

"So when will you leave?"

"Around June 1st," I said. "I have to make some arrangements, and pack up what I will take and give away what I won't."

More silence.

Finally, she stood up and said, "Good luck."

"Thanks."

Elizabeth stepped over and held out her hand, which almost broke my heart.

Before I could reach to take it, she suddenly threw her arms around me, and kissed me.

It was fierce.

It was fiery.

It was passionate.

It was a shock, Father Thomas, let me tell you. But after a—very short—moment of surprise, I put my arms around her and kissed her back.

I don't know how long we stood like that. It felt like forever, and it felt like only a second. Elizabeth broke the embrace and pushed back from me, taking her hands to smooth her hair and tuck it back behind her ears.

She looked down at the floor, then looked up with a wry grin on her face.

"It would never work between us while I am married, and I won't leave Fred."

Her voice was calm, and matter of fact. A voice that killed dreams.

"You are Euterpe," I finally managed to say. "You are my muse. I am my best because of you."

Elizabeth shrugged.

"Thank you for that compliment," she replied. "But I think you will have a new muse now." I looked at her in surprise. She continued with, "I think Princess Kristina will be your muse from now on, one way or another."

I shook my head, unable to speak.

Elizabeth stepped closer, rested a hand on my cheek, and whispered as the tears began to trickle from the corners of her eyes, "God go with you, Jude. Be well, be happy, be magnificent. And think about me from time to time, if you can stand it."

She pressed her fingers to her lips, then pressed them to mine. A moment later, she was gone.

I don't remember much about my last days in Grantville, Father. Just a few things: my last day at school, where the students conspired with the teachers to throw a party for me; playing the organ at St. Mary's church one last time; giving my keys to Johannes Fichtold and telling him the house was now Casa Zenti e Fichtold; watching over the back of the train car as the train left Grantville and headed for Halle.

I didn't see Elizabeth again.

So I am in Magdeburg now, Father Thomas. The work is hard. The work is challenging. The work is magnificent. The plans for the academy building have been drawn up, and construction will begin soon. We have a number of students already, and classes have begun in the old Franciscan monastery on the east side of the old part of Magdeburg. It will do for now, until the main building is ready.

I look forward to each day, knowing that the more we teach young musicians about the music of the future, the more they will take it and make it their own; not to slavishly copy it, but to make it the fertile loam in which they will plant their own ideas and dreams. I will not hear the flowering of the interbreeding of our traditions and the future's, our sonorities and theirs. That will happen maybe two generations from now, maybe more. But the symphonies that they will write, the instruments they will invent and build, the songs they will sing will all be so much greater, so much grander than I can even imagine. Only the mind of God can hold that vision, dear Father. But I know it will happen, and I know that it will be glorious. In this, I can only agree with the so-called Reformers, Father: Soli Deo Gloria.

As for me, I am content. I have my work. I have my challenges. In fact, I am nearing completion on the Brutus, which the princess asks about every time I see her. I hope that it will be the first opera performed in the new opera house, which has already started building. But there is time for that, which is a good thing, because I shall have to set it aside for a short time. You see, I recently received a new commission, communicated through Maestro Landi. It seems I am to write the celebratory music that will be used to welcome the newly-appointed Cardinal-Protector Lawrence Mazzare when he returns to his see. I have just started thinking about it, but already I have a few themes running through my mind. Imagine that!

So I am well, Father. I am writing music. I am furthering the cause of the new music. So I should be happy. But I must confess, Father, that late at night, when I am alone, I still feel Elizabeth's kiss; I still feel her body pressing mine; I still feel her fingers touching my lips.

I have the new muse, but I miss the old one.

God will deal with that as He wills. Who knows, I may go back to Grantville from time to time.

But in the meantime, Father, it is past time to end this letter. It is the longest one I have produced yet. I hope in it you will find cause to be proud of me, to wish me well, and, of course, to chastise me at least a little. I don't know what I would do if you did not scold me from time to time.

May the Lord give you peace and joy, Father Thomas.

Your servant and student,

Giacomo Carissimi

****